The Border Line

An experimental documentary about the Turkish-Syrian border.

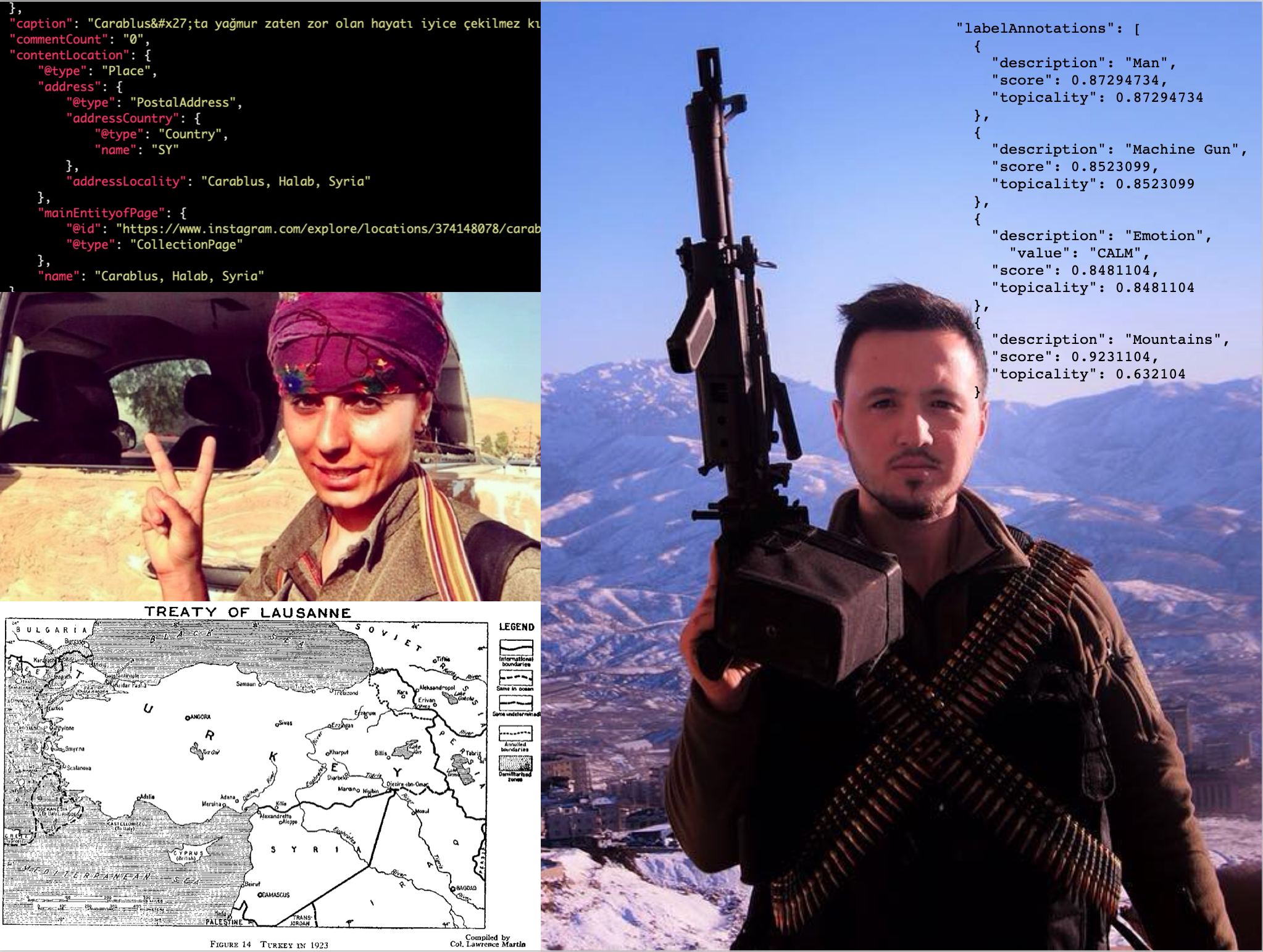

The Border Line is an experimental documentary drawn from all the Instagram posts along the Turkish-Syrian border between 2017-2019. The work questions how to see and chronicle migration and war through the lens of an expansive social media archive.

The Syrian civil war recently reached its grim 10-year anniversary. Throughout this crisis over 3.5 million refugees fled across a 900km border separating Syria from Turkey. A large number of these refugees used smartphones to map their routes, communicate with each other, and document their experience.

Utilizing the technique of data scraping as an artistic practice, the Border Line explores the narrative traces left in the wake of this migration. It asks what is at stake for history and witnessing when such a crucial collection of images are locked away in corporate databases and invites the viewer to consider the complicated lived experience of this place through the intimacy of videos made by bored truck drivers waiting to cross the border, Italian war tourists hanging out with Kurdish fighters, or a father brought to tears as he sends his daughter off at a wedding.

Artist’s note:

In 2015 a three-year old boy named Alan Kurdi lay dead on a beach in the Turkish resort town of Bodrum. The image of his body, face down in the sand, was published in newspapers across the world. When I saw this picture, I was sitting comfortably in an office in New York, a world and an ocean away. As is sometimes the power of these images, I could not get it out of my head. As my mind became filled with images of the encampments around Calais, of overfilled rafts rocking frighteningly on the Mediterranean, of internment camps in Lampedusa, I felt an urgent need to learn more about the lives of the people setting out on these vast and perilous journeys. When I learned that mobile phones were a crucial tool in the migration–Google Maps to trace border crossings, Whatsapp to communicate, Instagram and Youtube to document–the phone in my hand became a thing transformed: somewhere, perhaps just a tap or two away, were the same screens that were being used by migrants on their journeys.

Through chance I came upon an Instagram post from a house along the Turkey-Syria border in which an old woman was taking candy from a bag to give to a child. The woman kept pushing the excited child away as she searched through her bag with an aloof warmth that met the child’s eager eyes. At this moment I knew that there was an incredibly valuable and interesting archive of life here and I set about building a computer program to download all of the public images within 5km of the Turkey-Syria border. What would the migration crisis look like from this vantage? Visually this region is represented in the Western press often with images of horror, but here was a rich world of life’s quotidian rhythms as well.

I became fascinated by what a cinéma vérité could look like that emerged from the servers of internet giants. Like closed cities, archives from companies like Facebook (the owner of Instagram) are restricted areas that cannot be easily visited, instead being cordoned off for the consumption of the machine learning algorithms that generate the company’s trillion dollar market value. For Facebook this content is perhaps just a commodity, but it contains multitudes, the observed moments, the ideas of self and other, the sudden spark of emotion, listless boredom, revving the engine of a dirt bike, feeling the vibration as you turn the throttle, a vista so grand you skim over the surface, a struggle to capture it all. What do these closed archives mean for history and storytelling?

I spent the Corona lockdown manually reviewing over 100,000 videos and in the process developed an intimacy and familiarity with a place I had never been but had read so much about. I wanted to share this experience with the viewer by creating a poetic narrative that traces the border from east to west and in so doing, I hope, also to complicate and transform the audience’s understanding of the war and the lives caught up in it.